The following account is the result of recent conversations and on-going collaboration between Moussa Amine-Sylla and Nick Mahony, who are members of Community Organisers and work together on several projects. Here Community Organiser, Trainer and Community Organisers Trustee Moussa Amine-Sylla reflects on recent experiences of community organising in Tottenham, North London.

As Sharon Grant OBE (Chair of Public Voice CIC, Director of Bernie Grant Arts Centre, widow of Barnie Grant) commented to me recently, some of the strongest forms of solidarity are forged in situations of crisis. She gave the example of the relationships and movements formed at the time of the miners strike and how many of these ties still endure to this day in Tottenham.

When the UK ‘lockdown’ was initially put in place here in mid-March and the government really emphasised we were in the midst of a pandemic, the situation here felt really grave. The Prime Minister was telling everyone that people were going to die before their time and lots of people were, understandably, shocked and worried.

The government had clearly opted to pursue a particular strategy. By framing the situation as a public emergency, instructing people to go home and not leave unless absolutely essential and by ordering most shops and community services to close immediately and until further notice the government set the scene for the UK to become a kind of war zone. Local authorities and local communities were caught off guard and the usual sense of community almost instantly disappeared, at least for a time.

Forced devolution

The lockdown thereby set in train a kind of forced devolution. Busy high streets shut down, high street workers stayed at home and the local government authorities in Tottenham almost entirely vanished overnight.

Initially the local authority only had one phone number and about 50 people still on call. This wasn’t nearly enough.

It took the council two weeks to start to get organised. Eventually they put 200 people together to answer calls and created some additional phone numbers. Need was localised so they had to begin to organise by locality, rather than borough wide. However, what quickly became apparent was that the local authority didn’t have an effective front-line, which meant the council had little intelligence about what was really happening: which pharmacists were and were not open, which retailers could deliver, which local health systems were still working and which weren’t etc.

I had been working with the Council for some years and didn’t stop working or go anywhere when the lockdown began, so I had local people calling all day every day telling me what was happening to them, it was incredible. And there were plenty of other people, like me, who also didn’t leave the scene, which meant we were the people that started talking to each other and to others in the area where I work. We walked the streets to find out what was going on.

Unthinkable relationships

It was in the absence of local authority control and in this extraordinary context of public emergency that this entirely unforeseen process of forced devolution process happened before my eyes, whereby official and organised forms of support largely ceased and local people had to rapidly form new relationships because of the urgent need to survive.

(Photo: Sharon Grant OBE)

Before the pandemic many people didn’t have quite the same immediate needs they recently have had and they also mostly didn’t have the time to take action. The lockdown meant normal time and routines stopped and every day became more or less the same.

This was a situation in which communities needed to be re-connected and re-built and this got underway as soon as the lockdown began, completely beyond the control of local professionals or any kind of top-down ‘strategic’ plan.

None of this was in any way helped by a complete lack of reliable information. Local government had been ‘ghosted’ (suddenly disappeared) and the news on TV didn’t represent reality here either. It was only through connecting, through conversations taking place and relationships forming that a clearer picture began to emerge about what was happening, what was needed and what the priorities were.

Sharon Grant OBE believes that the current crisis, sparked by the outbreak of Covid-19 and which also shines new light on deeper and longer standing forms of inequality, could provide the impetus needed to help rebuild historical relationships of solidarity and build many new forms of solidarity too.

I agree with this analysis, especially as we haven’t seen any increase in burglaries or the looting of any shops here. What I see instead are food banks springing up, shops giving food away, small and large stores donating their stock to those that need, local union members connecting with local community organising and much more besides.

Sharon’s views about the forging of new solidarities have therefore already been reflected in my observations and experiences here over the last few weeks. It’s not just that social distancing is unnatural to most people and people have needed to continue to go out, what we’ve seen here is people (re)connecting and forming relationships in a whole range of new ways, despite all the difficulties.

I’ve seen people who have never spoken to each other before saying hello for the first time and asking each other if they are OK. I’m seeing people queuing at the post office exchanging stories. I’ve seen mutual aid groups forming too.

The starting point for these and the many other new connections has been the need to survive. This has meant people needing to find new ways to get together to understand and respond to what’s happening.

There’s been a kind of ‘Mad Max’ feel to some of this. The mutual aid work has been happening in areas that don’t have access to lots of resources so they’ve just had to organise for themselves. People haven’t been able to wait for the professionals to step in and support them, or for the usual agencies to intervene, these infrastructures have broken down.

I recognise that before this crisis the local council had already lost a lot of money and people were already struggling. Now the council is losing business rates and parking revenue and there was already a pre-existing funding deficit.

Article 44 of the 1996 Employment Rights Act, which rightly places a high level of accountability on employers to keep employees safe, will be a headache for local authorities who will find that the easiest thing will be to make employees redundant. So as this crisis continues there are likely to be less council workers, plus a reduction of public services as well as less money available to support anything in the community.

So things are going to get a lot worse now. People in this community are going to have even less choice in the situation, which means they will need to continue to respond for themselves.

What we’re going to see is an on-going shrinking of local authorities, combined with the lack of a future development strategy and a withering local government infrastructure. This will result in more and more forced devolution: experts and council services are simply going to be scrapped in many contexts and, with this, more and more people will be needing to do things for themselves.

Pasta sauce and Oysters

My hope in this new context is that people realise, collectively, that there is not a lack of resources, but that the problem at the moment is with how societal resources are unequally allocated and used.

Disconnected communities, a lack of cohesion and growing injustice in our society are all way more costly than any lack of government control over local people.

Individualism doesn’t work - in healthcare, safety, security, justice, socially or with the environment. Unity, cohesion and collective organising is what we need; and acknowledging difference and diversity makes for a much more healthy organising culture.

Where there is no connection, no public accountability, no justice and no real forms of participatory democracy it is damaging and costly and there will be more health issues because isolation kills. We can’t return to the status quo.

It’s not just that there is no money, if society is to get better and be more healthy the community has no choice now but to build.

What gives me hope in this context is that in the last few weeks I’ve already seen countless previously unthinkable relationships beginning to be forged. It really does feel like anything can happen.

For example, a guy came here to The Selby Centre a few weeks ago, having volunteered as a driver as a result of his involvement with a mutual aid group in another part of Haringey. He had a beautiful car. He opened his car boot, it was full of food. Alongside donations from members of the mutual aid group, he had bought lots of food himself from Marks and Spencer. When he opened the side of his car it was so over-laden with food that a jar of pasta sauce accidentally fell out and broke. This then happened again with another jar. For a joke, I told him that we had strict policies in place and needed to take a photo of donors so we could post these on our social media. He said he didn’t want his picture taken, but allowed me to take a picture of the food in his car boot instead.

I asked him his name? He said his name and he was a really well known actor and comedian. I hadn’t recognised him and hadn’t expected him to be such a humble person.

Since we started the food hub here we’ve received donations of all kinds of food, including lots of basic provisions and essentials and sometimes even gourmet foods such as Oysters.

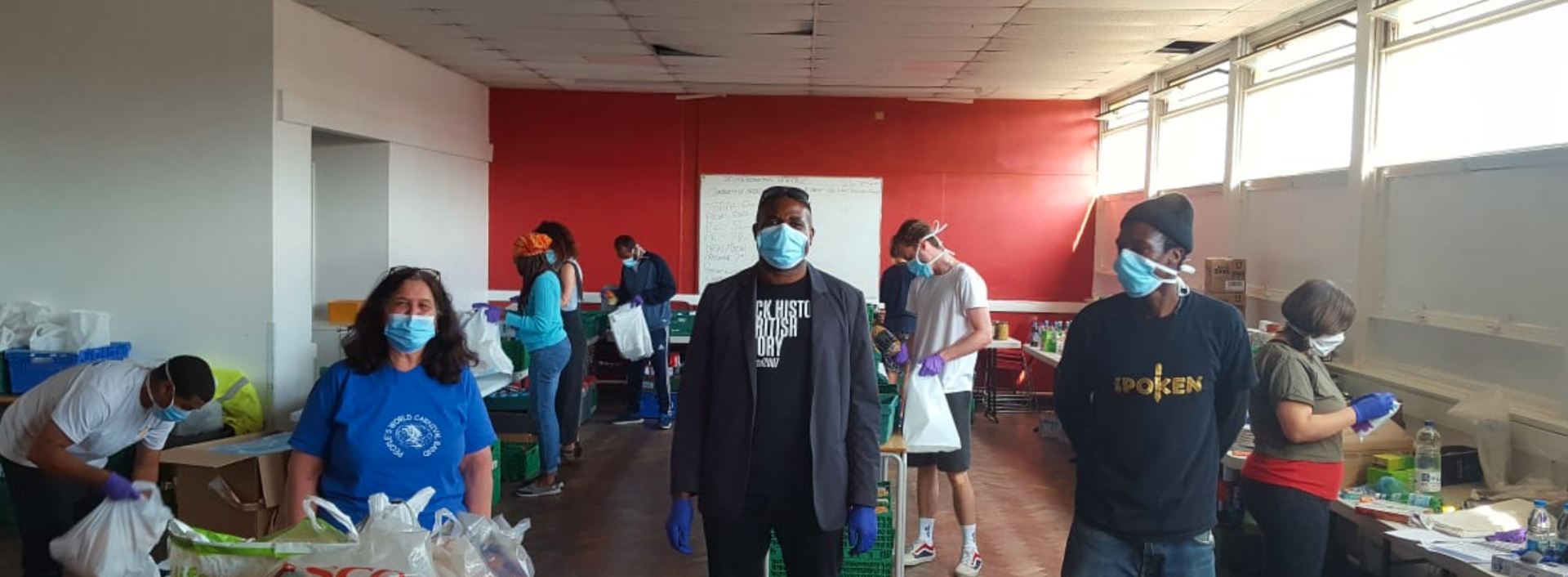

The Selby Food Hub project came about as a result of the Selby Food Bank being unable to operate in the usual way after lockdown. The staff at Selby realised that this would have immediate and negative effects, so a proposal for an independent alternative food hub was quickly developed following discussions between the Selby Community Organisers and the Selby Projects Officer. This was then put into immediate effect with the aim of alleviating the food poverty and insecurity in our community which was being exacerbated by the pandemic.

None of this could have happened if staff at Selby Trust had not already nurtured, over several years via the community organising approach, a network of social activists in the local area. This enabled us to quickly and very successfully implement this initiative in collaboration with a pre-existing group of passionate and committed local people. And it was through the strength of these relationships that we were also able to link with the 30+ mutual aid groups that quickly emerged after the lockdown. The food hub became one point of focus around which some of this new social action could be organised.

In this context we were also engaged by Age UK, which has never happened before. But my favourite experience happened as a result of the local CWU branch secretary getting in touch with us. We talked about how local union and community organising activities could be better connected and he wanted to help with the new food hub, which I was in the process of getting up and running. Not long afterwards a Royal Mail van pulled into the Selby carpark laden with food, donated by local CWU members, who he had been able to quickly mobilise.

Since then we have begun discussions about how we might extend and develop this relationship. Both of us are interested in the idea of trying to create a new food cooperative that could be run by local workers and the community.

Why shouldn’t people have their own Marks and Spencers? This could really benefit people here – the TUC and others should support this kind of thing.

We need to nurture these new relationships of solidarity. We need to strengthen them, learn from what’s happening here and help them endure.

Supporting diversity, self-organisation and community control

I’m not sure there’s really anything that the local authority can do to help me with what we’re doing here. What I need is a shift of mindset, culture and resources. Local authorities don’t trust communities, don’t generally work with the unions, can’t and shouldn’t manage mutual aid – local authorities are still highly paternalistic and think from an authoritarian point of view about how to manage, govern and control.

Now’s the time to nurture, trust and invest in the intelligence of the people and the community. If this isn’t going to happen and local authorities are going to continue in the same old way, what we’ll get is the same old problems continuing to be endlessly reproduced.

But what we have here, at least for the moment, is is a pretty rapid withering of the dominant paternalistic monoculture of the local authority, which has been quite unexpectedly pitted against the diverse culture of people who are self-organising in Tottenham – where we have Latin American, Kurdish, Gypsy, Black, Eastern European and many other people coming together around food and in the desire to self-organise and provide mutual aid.

On the days of the foodbank these people all queue together chatting, getting along with each other while also keeping their distance, 2 metres apart.

Much of what I’m trying to do here, with many others, builds on what I’ve learnt over the last three years developing a project called Spoken. With Spoken, cultural diversity is the starting point for organising in the community, using spoken word and poetry as a catalyst for imagining alternatives, generating collective action and supporting democratic participation at the grassroots.

It’s still early days. In terms of developing the alternatives needed here and anything could happen in the weeks and months ahead. But what I do know for certain is that now is the time to stand together in solidarity with the aim of collectively creating the alternatives that will work best for the people and the community here in Tottenham.

Orthodox – monocultural and paternalistic – approaches won’t work, they will reproduce the status quo, in large part because they are driven by the authoritarian and top-down culture of the father.

We don’t want or need this culture.

What we want instead is to work together, in all our diversity, to organise and create alternatives. That’s why continuing to strengthen and build solidarities here is key. We want to realise this better way of working together for the common good.”

Moussa Amine-Sylla is the Lead of Community Organising, Selby Community Centre and has trained 183 Community Organisers; Moussa supports the local community group network in Tottenham and is a Director/Trustee/Board Member of Community Organisers; member of the Movement for Cultural Democracy; and co-founder of Spoken, a cultural platform for spoken word, poetry and culturally democratic community participation in the Tottenham area.

Nick Mahony is a researcher and member of Community Organisers; he’s also Co-Founder of Movement for Cultural Democracy; Development Coordinator for Raymond Williams Foundation; and researcher at Municipal Enquiry, a new collaborative project founded with the aim of supporting alternative forms of local power, participation and democratic control.